Excerpt from The Beauty of the Mountain p59

In November 1985, at Rajghat, K told me that he still had some months to live. When I reminded him that he had promised us he would live another ten years, he only raised his arms as if to say, What can one do? K’s health had started to deteriorate at Brockwood. The regular walks that he took became shorter. The walk through the Grove and across the pastures and fields, which entailed climbing over a fence, he did not do anymore. Apart from that, he was as active as ever. Once he told me: Je travaille comme un fou! (I am working like mad!)

K had been very enthusiastic when he said to me at Brockwood in 1984: You come with us to India. How could one resist? He invited me to live close to where he lived and, for health reasons, to eat the same food. You stay with us! he said when I was to go to Rishi Valley, Rajghat and Madras for the first time. Later that year, in Schönried, he asked me to live with him. I knew what that meant: to drop everything, and I was not ready for it.

Now, in the autumn of 1985, I was travelling with K on his last journey to India.

It was an early morning departure from Brockwood. The day had not yet dawned, yet all the staff and students, about one hundred people, had come to the west wing and were waiting at the bottom of the staircase to see us off. K shook hands on his way to the door. The atmosphere was solemn. A premonition hung in the air that this might have been K’s last visit.

Dorothy Simmons, the former principal of the School, drove us to the airport in her car. K and I sat in the back, with Mary Zimbalist in the front. At the start there was rain, but it soon stopped, and Dorothy forgot to turn off the wipers. They began to scrape across the dry windscreen. I became tense and would have liked to say something but instead waited for a reaction from K. And, as so often happened, his response was not what I would have said. It was simply It’s stopped raining, and Dorothy immediately turned them off.

At the airport the moment of parting brought tears to the eyes of the women. Dorothy and Mary were staying behind, I was the only one flying with K. Rita Zampese, Lufthansa’s public relations manager in London, led us through to the lounge. We found ourselves sitting near a group of men and women, business people probably, who appeared very self-absorbed. They were talking loudly, smoking and drinking alcohol. K looked at them with wide eyes, and the expression on his face was one of astonishment and mild horror, although he was not the least bit contemptuous.

We had to change at Frankfurt, and I remember with what joy K travelled on the fast electric shuttle between terminals. On the larger plane, he had the single seat at the front and to the right, which only Lufthansa was able to offer. By contrast, I found myself sitting by a gentleman who was reading a newspaper and listening to music at the same time. What’s more, he made hand movements as a conductor might. He, too, was self-engrossed and showed not the slightest interest in his neighbours – in this case, K and me. It was night-time when we flew over Russia and Afghanistan. On the plane K said: I’m glad we two are alone.

After arriving at Delhi, K went with Pupul Jayakar to stay at her house. I went to a hotel, where I was the only European but also the only one wearing Indian clothes. Every day at sunset we met at Lodi Park. It was always at sunset, because K had once suffered from sunstroke and had to keep out of the strongest rays. At the entrance there was a kind of turnstile, which glistened with the sweat and dirt of many hands. I would open it with my foot, and K would exclaim Good!

The park was well kept, with many trees, lawns, waterways and bridges, and buildings from pre-Mogul times. At dusk innumerable birds would gather and settle down for the night. The noise they made was deafening. Occasionally Nandini Mehta or Radhika Herzberger’s daughter, Maya, would join us on our walks, as would Pama Patwardhan.

One man in Lodi Park recognized him and approached rather aggressively, demanding, “Are you Krishnamurti? You should stay in India! Here are your roots!” K replied: I am nobody. Then he raised his open hands to me and said: You see, they have a fixed idea and stick to it. Despite such incidents, K was friendly towards everyone he met and especially so towards the poor and those who were normally ignored by others, such as the ice-cream vendor at the entrance to the park.

K once mentioned that many years earlier he’d been asked by several followers of Gandhi what he thought about the caste system in India not allowing certain people into the temples. He replied: It doesn’t matter who goes in, because god isn’t there. He spoke about this in 1975.

When I mentioned this quote to an old friend, she told me another such story: A beggar is crying in front of a temple, and God comes along and asks him why. The beggar says, “They won’t let me in the temple,” and God replies, “Me neither.”

Travelling, and the frequent change of climate it entailed, exhausted K, and his health deteriorated in Delhi. He did not sleep well and he ate very little. He used to say that he would have become much older if he hadn’t had to travel so much. He once told us that many years earlier he had travelled by train from New York to California, taking three days and nights. I asked him if this was tiring, and he said: Yes, very much.

From Delhi I went on my own to the Krishnamurti Retreat Centre near Uttarkashi in the Himalayas. A school would be established there some years later, but it was closed after the people responsible for it encountered difficulties. In any case, K hadn’t wanted to have a school there but rather a retreat centre.

On the plane to Varanasi, K kept the window shade down because of the bright sun. But time and again he would open it to look at the white peaks of the Himalayas. We agreed that the mountains were really something!

He told me that once, as a young man, he had been clambering around the Zugspitze, in Germany, in casual shoes. A mountain guide who passed by with a group of alpinists on a rope noticed K. After scolding him, the guide tied him to the end of the rope and led him down the mountain. K told me he had not been afraid and could have descended safely by himself.

I was overwhelmed with the atmosphere at Rajghat in Varanasi. Here one can especially sense the enchantment that appears to exist in all of the places where K lived. It can be felt at Brockwood, Rishi Valley, Vasanta Vihar – K’s home in Madras and the headquarters of KFI – and Ojai. One could also find it at Chalet Tannegg in Gstaad and both Pupulji’s government house in Delhi, which was full of ancient sculptures and other works of art, and her apartment in Bombay. The surroundings in all of these places are strikingly beautiful and immaculately kept: islands of serenity amidst the turmoil of the world, full of trees, flowers, birds and butterflies; there is a kind of sacredness about them.

Walking around the grounds of the School at Rajghat, one comes upon several archaeological excavation sites. The campus is situated in one of the most ancient parts of Varanasi, called Kashi, and presumably there were temples, parks and royal palaces there 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. Beyond the excavation sites a canal carries sewage from the city into the Ganges. The stench was noticeable all the way to the house where K was living. He laughed when Pupulji assured him that a new sewage system would be built in the near future. Apparently this promise had been made many times, and when I visited the following year nothing had yet been done. It was only during my visit at the end of 1988 that I noticed that construction of the huge new canal system had begun.

At Rajghat my room was underneath K’s. As soon as he arrived he began intensive dialogues (see pg. 68). At sunset he would walk several times around the School’s large sports field, accompanied by friends, whom he jokingly called his bodyguards. Even during these recreational walks he continued his discussions with them. His legs were becoming very weak, however, as he himself said, and after one walk he fell forward on the steps. His companions wanted to help him up but he refused to let them, saying: If I fall on the steps that is my affair!

When K could no longer walk quickly, I would go on my own, circling as briskly as I could. After such walks he would ask me how many rounds I had done and how long I had taken. When I told him that I had broken my record, he responded enthusiastically. Somebody must have complained to him, though, about this crazy guy chasing around the sports field, because he said in a meeting with friends: He just wants to keep his body fit. What’s wrong with that?

It was customary to invite people for lunch with whom K would hold intense conversations. At Ojai and Saanen he would sometimes converse until 4 o’clock, even when he had given a public talk that morning. He liked to question those invited about their areas of specialization. Thus he was well informed about current developments in many fields, including politics, education, medicine, science and computers. Once the vice-chancellor of a university and his wife were invited to have lunch at Rajghat. K noted sadly that the man never once smiled at his wife, nor even looked at her.

Every once in a while, Vikram Parchure’s wife, Ambika, would bring along her lovely 3-year-old daughter. K would say to the little girl: Don’t forget that I want to be your first boyfriend.

During the time that we were at Rajghat, a great many religious festivals were celebrated which were often very noisy. The temple next door would resound with fireworks, drums and singing late into the night. At 4 o’clock the next morning the celebration would start up again. There was also an adjoining mosque from which we could hear the greatly amplified singsong of the muezzin during our walks. None of this seemed to disturb K. If the muezzin had not yet started his calling and noticed K approaching, he would walk up to the fence to shake K’s hands affectionately.

At this time, part of the Indian film The Seer Who Walks Alone, a documentary about K, was being shot at Rajghat. K had told the director: I’ll do anything you want me to do. One scene shows K standing on a hill above the Varuna River, outlined against the setting sun like an ancient sculpture. He walks over the narrow bridge across the river and along the path to Sarnath, where the Buddha was said to have walked.

K was once with Donald Ingram Smith in Sri Lanka, a predominantly Buddhist country, and said: If you listened to the Buddha, you wouldn’t need Buddhism.

When the time for his public talks drew near, K seemed to gain new energy. He gave three talks and held one question and answer meeting at Rajghat despite obvious signs of physical weakness. He also had three dialogues with Panditji in the presence of thirty or forty others in the upper story of his house, which are recorded in the book The Future Is Now (also titled The Last Talks). Kabir Jaithirtha has told me that Panditji once asked K to put the teachings in one sentence. K replied: Where the self is, there is no love; where there is love, there is no self.

During these talks, one participant stood out through the clear and simple manner with which he communicated with K. At the time, I didn’t know that this was P. Krishna, the new school director. K, despite poor health, was concerned with every aspect of the appointment of the director and gave all his time and energy to the matter. He invited Krishna and his family to lunch and talked affectionately with his wife and children; the grandfather came along once as well. As usual, K was interested in the practical details too, like the appropriate salary for the new director and that he had the use of a car. He felt enthusiastic about Krishna who, as a well-known physicist, had worked in the USA and Europe. He told me that when he had asked Krishna if he would take over the School, Krishna deliberated and then announced, “I would be delighted.” This was very fortunate, as there were then quite a few difficulties there.

Once we were sitting together with Krishna’s lovely teenage daughters, and K told me in French: Do you see how different they are? Then he said to the others: I’ll translate. I said, You should not marry while you are too young.

Finally, it was arranged that K would take his meals in bed, as he had hardly any chance to eat during these lunchtime conversations. He had told me once that he never had the sensation of hunger, though he could eat properly nevertheless. But these days, being unwell, he ate very little indeed.

After a walk one evening K asked R. R. Upasani, who intended to retire from the Agricultural College at Rajghat, where he was principal, if he would stay on to work for the Foundation. Upasani agreed to continue as long as K was there. I said to K, “Upasani should stay on even when you are not here.” K immediately asked Upasani: Sir, stay another year or more. Upasani was so moved that he wept. It was getting dark, and suddenly K asked: Where is he? as he could not discern Upasani in the darkness. It marked the onset of a kind of night blindness.

While he was at Rajghat, K several times addressed the subject of sex. He pointed out that of course we would not exist if it were not for sex, which was simply a part of life. Somebody told K about a cross-cultural wedding where the guests were already gathered when it was discovered that the bridegroom had disappeared without explanation. K often referred to this story, wondering at the girl’s apparent determination to marry despite the great difficulties inherent in such circumstances. At one point he wondered aloud: Did they have sex? The innocence of this remark caused considerable laughter among those present.

There are two other, rather random memories that I have regarding K at Rajghat. When he sat with several Theosophists in Annie Besant’s old room on the campus, he asked them: What shall we talk about? Then he went on: Oh yes, I’ll tell you a few jokes. Also, Annie Besant’s coffee service was still in the room, but K did not have any recollection of it nor of the room itself. That coffee service must have been there for over sixty years.

After the public talks we flew via Delhi to Madras. At the time of our arrival the weather was pleasantly warm. The palm trees and flowering shrubs moved gently in the fresh breeze. As we drove, in a cabriolet, from the airport to Vasanta Vihar, I suddenly felt as if I was returning home. At that very moment K remarked: It is like coming home!

Later as we walked along the beach we witnessed the surf crashing thunderously onto the luminous yellow sand. There was a strong wind blowing but delicately-violet clouds hung in the sky. Against this background the full moon rose from the ocean just as the spectacular sun set opposite, which was mirrored for us on the surface of the Adyar River.

A few years ago while walking along Adyar Beach, I met a fisherman named Karuna Karan. He spoke English quite well, as he had studied for a time at the Theosophical Society’s Olcott School. He told me that when he was a shy little boy, K had once grasped his hand and taken him for a fast walk. He claimed that almost no one could keep up with K. He also said that some villagers had asked K to look in on someone who was ill, and when he entered the person’s hut their fever disappeared.

At one point at Madras in 1985, I went to his room and he was looking at a newly published book whose cover image was a photograph of himself. Somewhat amused, he pointed to the cover and remarked: He looks a bit sad.

After only a few days in Madras we left for Rishi Valley. We started out early and this time saw the sun rising as the moon simultaneously set in the west. We were travelling in a new car that was decidedly more comfortable than the old American one we had used on previous occasions. As usual, the car had been made available by a good friend, T. S. Santhanam. We didn’t stop until we had covered half the distance and the first hills were coming into view. The morning landscape was immensely peaceful. A motorcyclist, stopped beside the road, was amazed to see K there. K was no less astonished that someone should recognize him in this isolated spot.

K conversed with our friendly chauffeur about his family and insisted that he should send his children to Rishi Valley School. Later the man’s son did indeed study there.

Radhika lived on the same floor as K at Rishi Valley. She and I would have breakfast in K’s dining room. Sometimes, when he was feeling stronger, I would go to see him in his bedroom to say good morning. One time I said to him, regarding Rishi Valley, “It’s almost nicer than Ojai, though it is similar.” To which he replied: Of course.

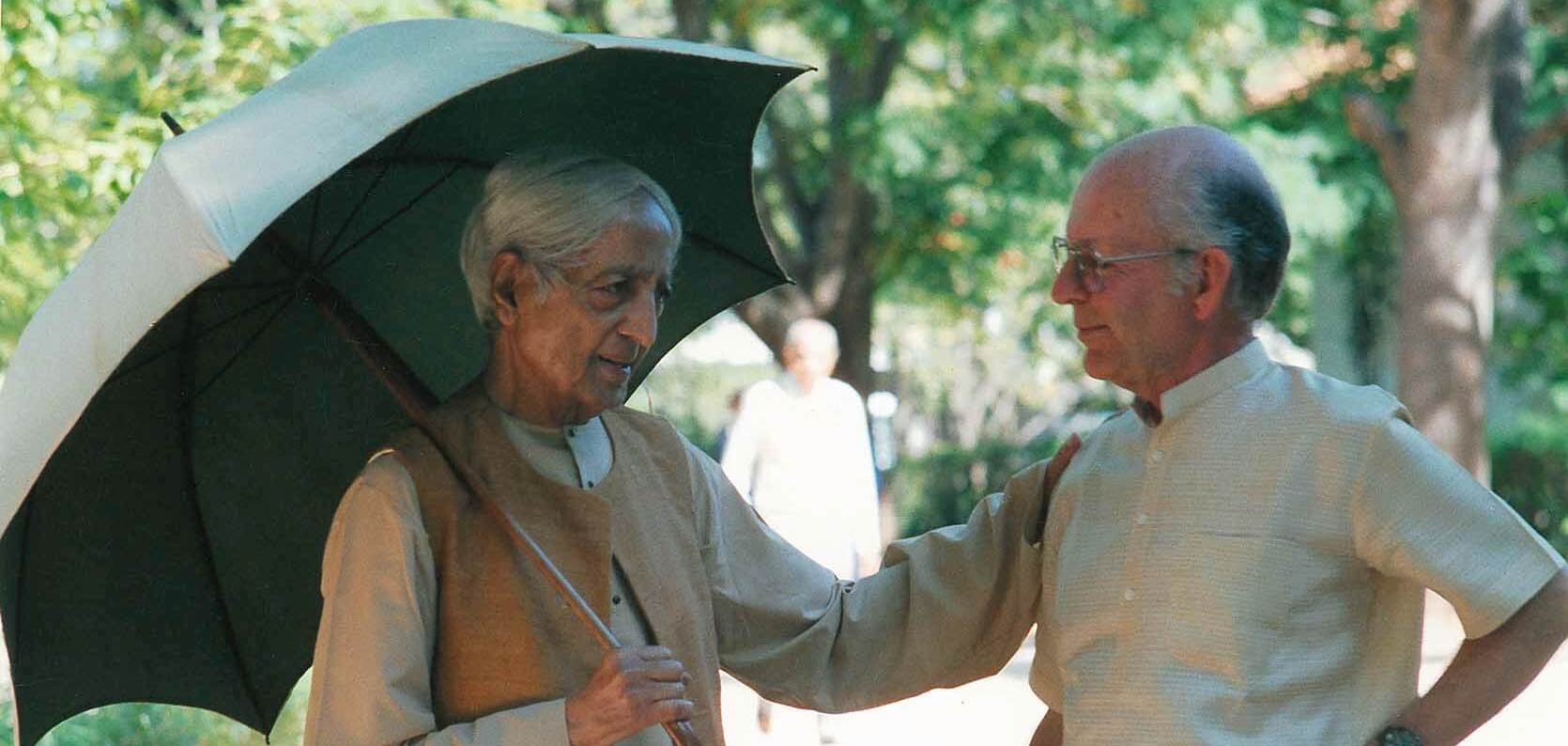

Because he was feeling so weak his daily walks were often cancelled, but he still had a number of meetings with studentsand teachers. During our last walk together at Rishi Valley, in December 1985, something happened. While I was looking with admiration at the lovely blue mountains east of the valley, K suddenly put his arm around my shoulder and said something like: My dear friend. Radhika was with us, and when she reminded me of the scene, I asked her to write it down:

“As a party of us walked down the road, I could sense that he was straining every nerve to keep up with the small group of younger friends that walked with him that afternoon. But at one point, when we had reached the cluster of rocks under what the Rishi Valley children call Uday rock, his demeanor changed. There was an unexpected lull and I turned around to see the tension and effort go out of Krishnaji; he was his still and contemplative self. A moment later he turned around and embraced Friedrich, calling him my friend. Later that evening in his bedroom, saying goodnight to him, I said, ‘Something happened to you this evening, didn’t it?’ Wearing the hooded look that came over him when he was approaching mystery, he said: Good for you to have noticed.”

Radhika’s use of the term “hooded look” reminds me of an occasion in the crowded dining room at Vasanta Vihar when I was sitting across from K and he suddenly caught my eye. How can I describe the flame that came from him? It was like a volcano bursting. The whole person was on fire. It reminded me of the sunset at Rishi Valley that K had described: You were of that light, burning, furious, exploding, without shadow, without root and word.49 I couldn’t stand this force, so eventually looked down. None of the other guests seemed to have noticed.

A similar thing happened at the table in the west wing kitchen at Brockwood in the presence of two other people. It was unlimited energy, an immense force that he emanated. Did he want to show us something? It seemed to express Wake up or Come over. It had urgency. He used to tell us Move! Move! Occasionally on our walks he would push me on the shoulder, which seemed to indicate the same thing. This reminds me of a walk at Brockwood when K was rising after tightening his shoes and I told him that my grandmother used to say at the end of a break, “Debout les Morts!” (“Rise, you dead people!”) This he enjoyed very much.

I would sometimes try to observe K to guess what he was thinking. But I couldn’t see anything; he was impenetrable. Perhaps because he wasn’t thinking. David Moody writes in his book The Unconditioned Mind:

“The conversation was coming to a close, and I gazed rather deeply into Krishnamurti’s eyes. He met my gaze completely, without any undue sense of modesty or confrontation. As I looked into his eyes, I had the uncanny sense that there was no one present, no structure of identity, on the other side. Whether this was a projection or a valid intuition I cannot say. I felt he was observing me as completely as I was observing him, and yet at the same time it was like looking through a clear window, with only open space on the other side.”

After teachers from Brockwood, Ojai and the other Indian Schools arrived at Rishi Valley for an International Teachers Conference, it turned out that K was able to attend some of the meetings. Because of his poor health, his active participation had not been planned, but it raised the discussions to a higher level. These talks, too, are included in the book The Future Is Now/ The Last Talks.

During his final two years visiting Rishi Valley, K spoke with the lovely younger pupils there, discussions that are available as MP3 recordings and on DVD. After one of the final discussions, K asked me: Did you see these boys and girls? They will be thrown to the wolves. His relationship with students and his views on education always fascinated me.

On one occasion at Rishi Valley we were talking with K about setting up an adult study centre. Suddenly a hoopoe bird came to the window and began pecking vigorously on the glass, obviously wanting to come in. K calmed it: All right, all right, I’m here, I’m here. Later Radhika told me that K often talked with the bird. She once entered his room and thought he must have a visitor, as he was saying: You are welcome to bring your children, but they probably would not like it here because when I am gone they will shut the windows and you will not be able to find a way out.

Another recollection of that visit to Rishi Valley is the time that a farmer driving a bullock cart invited me to jump up onto the back of it. It was a hard ride and I was gripping the side tenaciously. I was afraid that if the bullock took off I would go flying. We rode by K’s room in the old guest house, and I looked for him at his window. He didn’t seem to be there but later he said: You were really holding tightly to the bullock cart. I imagined him seeing me with a sixth sense, and others since then have told me similar stories.

On one walk at Rishi Valley, there was a beggar on the side of the road. K recognized him and shook his hand. Sometimes when villagers were walking towards us they would step off the road; K would try to get them back on. He was always concerned for poor people, and in a talk with students at Rishi Valley he described the long distances the village children had to walk to their school. He urged the Rishi Valley students to put pressure on their teachers to provide a bus for these children. To avoid this, one of the students said something like, “But you are the president, you could do something!” which caused some laughter. In 1984 at an International Trustees Meeting at Brockwood, K took Radhika’s hand and made her promise to establish so-called satellite schools in the villages. She did so, and there are now around forty of them.

The state of K’s health made it difficult for me to fathom how he could possibly give the scheduled series of talks to thousands of people in Bombay. I felt great relief when he had them cancelled. After he returned to Madras, I travelled with a few teachers from Brockwood and Ojai to visit The Valley School in Bangalore. Afterwards I myself returned to Madras for another week and joined K on some of his walks along Adyar Beach.

On one of my last ever walks with K, on the beach, we had just reached the house of Radha Burnier when suddenly he took my arm firmly under his and we walked at high speed around the house. I wondered if he was exorcising it.

Soon K decided to leave for Ojai. It would be easier to obtain medical treatment while staying at Pine Cottage, and he would have more tranquillity there. Scott Forbes, who had travelled with him from Rishi Valley to Madras, was the perfect person to accompany him on this journey across the Pacific.

After returning to Europe, I spent three weeks in the Swiss mountains and then flew directly to California, for Ojai.